It was probably late ’78, I was 13 or 14, and I was getting turned on to this new music that was punk rock. I felt I was late to the party because ’77 was the year it had broken and, being a kid, I’d missed that. At that age, things move fast. I’d heard the Pistols and we had DOA from Vancouver BC and I had a single of theirs, The Prisoner, that I loved.

There were a couple of older punkers – Kurt Bloch and Kim Warnick from The Fastbacks – who started to turn me on to lots of different things. Kim would make these mixtape cassettes and Scott McCaughey from The Young Fresh Fellows was our record store guy. That whole time was so great!

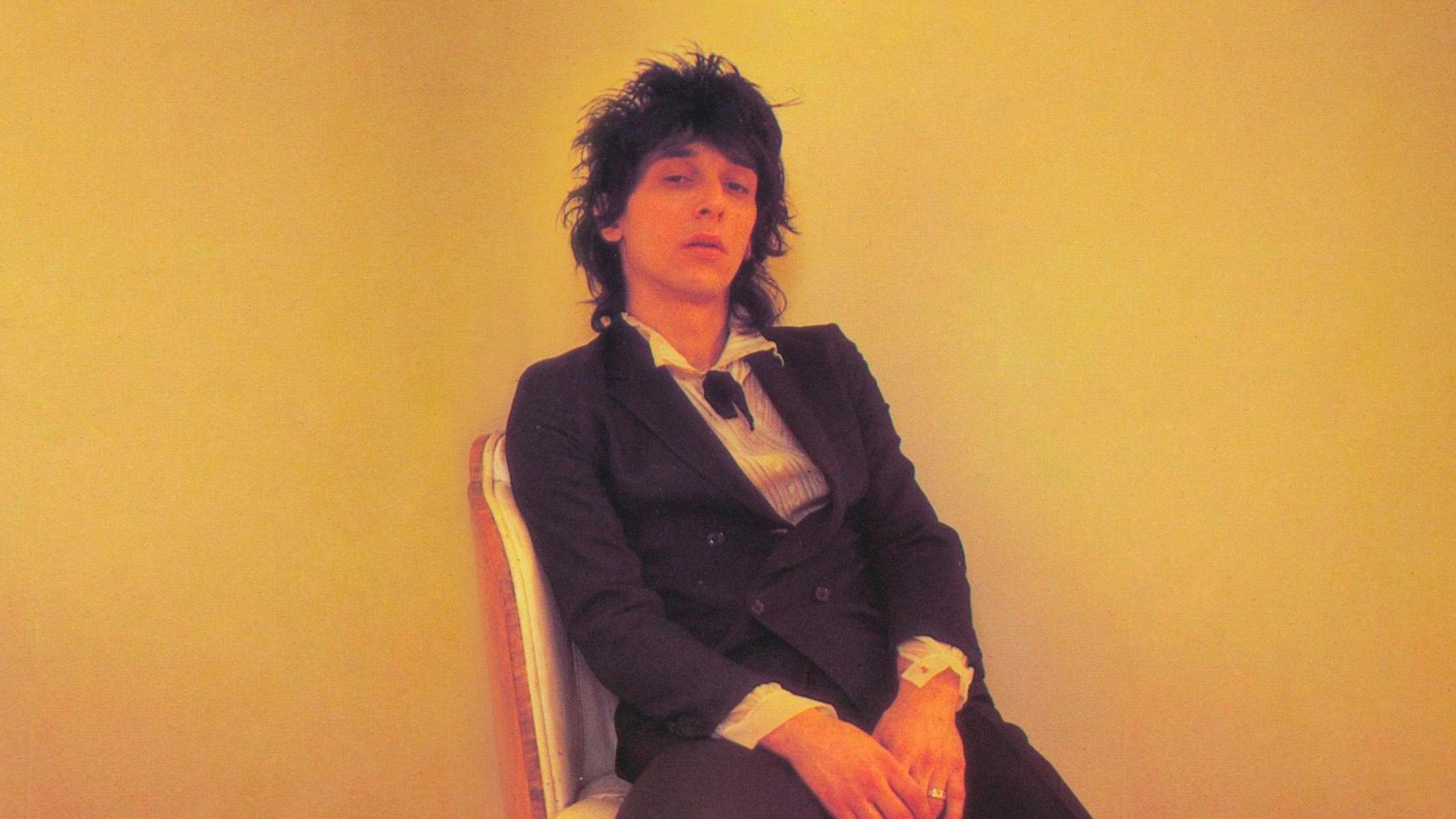

You mowed lawns and did a paper round to save your money, so maybe you could buy a record. So I bought records by the Pistols, Vibrators, Generation X, DOA, UK Subs and some singles from weird little scenes. But the bands were all foreign, really. With a band like The Clash, when they sang White Riot we didn’t know about the economic struggles of England. We learnt about it, but it was still quite alien. Then I saw the cover of The Heartbreakers album L.A.M.F., and I thought, ‘That’s what I want to be!’ I could relate to it and to Johnny in particular.

I heard the music and I really drew a straight line from Johnny Thunders to Steve Jones [from the Pistols]. I’d worked out that Johnny’s previous band, the New York Dolls, had come before the Pistols, so I figured that Jonesy had been totally influenced by Johnny. I’d heard the Dolls by then, too, alongside Slade, Sweet, T Rex, The Stooges and The MC5, but Thunders rose to the top, for sure. I learnt to play Pirate Love [the first song on L.A.M.F.] and it’s still one of the greatest songs of all time.