I caught up with him standing by the river and he told me he was going to kill himself. He pointed the gun at me, then brought it up to his head. He was shaking, sweating and crying. I was probably on speed or dust. I didn’t like where things were going. They could get tragic with a twitch of his trigger finger.

“You know we’re still brothers,” I said. “You know that.”

“Yeah, so what? I don’t care.”

”But I do care. A lot of people care about you. You crack us up, man. We love you.”

“I’m not so funny now, am I?” he slurred.

“C’mon, man,” I implored. “You don’t want to do this. So what if you’re not in the band? There are so many other things you can do.”

“Like what?”

“You’re alive, man. You’re a character. You’ve got more personality that most singers. I know you’re hurting, but we can’t talk or work anything out if you pull the trigger.”

He didn’t say anything, so I continued. “Put down the gun and we can figure something out.”

“What do you mean about me being a singer?”

“Put the gun down and we can talk about it.”

To my surprise, he dropped the gun and I picked it up.

Then Raybeez pulled out a box cutter. At first, I was worried he was going to slit his wrists.

“Nooooo!” I screamed.

“Blood brothers!” he shouted, and I understood.

He cut his palm, handed me the blade and I cut my hand. Then we shook. We were blood brothers for life.

At first, Ray was laughing, then he started sobbing and wouldn’t stop. It was a total release of desperation, depression and drugs. You could almost see angel dust leaving his body through his tears.

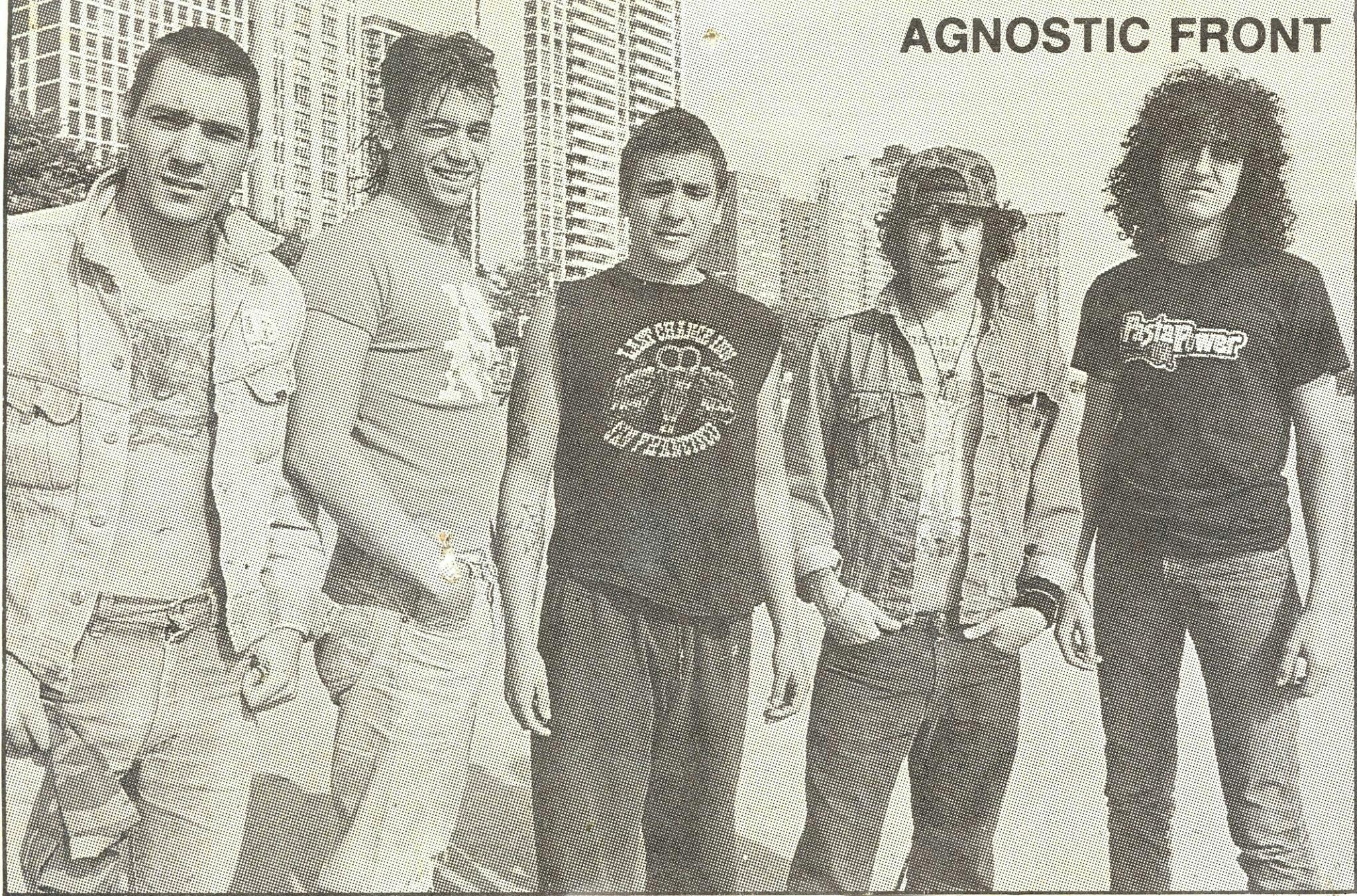

I got him back home and he was quiet. He seemed okay for the time being. I told him we had to move forward without him, but I promised I would help him form another band. He always had a tinge of resentment about being kicked out of Agnostic Front, but our friendship was stronger than his hurt feelings. And I was honest. I told him straight-up that he had great charisma and would be a better front man than a drummer, which was the truth. I proved it when we formed the band that became Warzone.